Some Interesting Historical Facts...

375 years ago in 1640, Greenwich was founded with the purchase by Robert and Elizabeth Feake and Col. Daniel Patrick from local Native Americans of the lands between Tomac Creek (Stamford border) and Long Meadow Creek (the tidal waterway off Greenwich Cove dividing Riverside and Old Greenwich).

The purchase contract, which survives today, notes the “particular purchase” of the lands currently consisting of Greenwich Point and the causeway leading thereto, by Elizabeth Winthrop Feake. This was among the earliest instances of a woman individually holding title to real property in the New World.

The Point was known by the Native Americans as “Monekewaygo”. Beginnning in 1640 with the purchase by Elizabeth Feake, the Point was known as “Elizabeth’s Neck”. Following its purchase by the Tods in the 1880s, the Point was known as “Innis Arden”, and since its acquisition by the town in 1945 it has been simply “Greenwich Point.”

Nomination of Greenwich Point to the National Register of Historic Places

The Greenwich Point Conservancy and the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office have partnered to nominate Greenwich Point and its historic resources to the National Register of Historic Places. The areas of significance that are the focus of the nomination include Recreation, Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Archeology. Greenwich Point has significant history and importance in each of these areas, and the discussion regarding these areas from the nomination is included below.

Recreation

Recreation is a significant theme for Greenwich Point, as evidenced in its initial development as a rural summer retreat for a successful industrialist following the trends established in other summer retreat locales, such as Newport. Despite the agricultural buildings constructed on the property, Mr. and Mrs. J. Kennedy Tod’s country estate, “Innis Arden”, reflected the burgeoning shift in land use along the Connecticut coast from the cultivation of crops to leisure activities. The Tods afforded the public limited access to portions of the Innis Arden estate during their tenure, presaging the later full public access after conversion of the property to a public park. The leisure activities at Greenwich Point, such as swimming, nature walks, and birding, have occurred from the occupation of Innis Arden to its present incarnation of the property as a park.

While the Greenwich mainland relied on agriculture throughout much of its history; the introduction of the railroad in 1848 opened the town both to working-class immigrants who established permanent residence and to affluent New Yorkers escaping the hectic urban scene for the temporary peace and quiet of the Connecticut countryside. Following the Civil War, the northeastern United States experienced an industrial boom that further stimulated the regional economy and that created millionaires. By 1870, artists were flocking to the picturesque Greenwich district, and, within a decade, they were joined by well-heeled New Yorkers who populated the area with country estates and grand summer “cottages.”

Others vacationed in luxury resort hotels built to accommodate affluent visitors.7 Among the wealthy New Yorkers attracted to the Greenwich vicinity were Mr. and Mrs. Tod. J. Kennedy Tod had emigrated from Scotland to the United States during the late nineteenth century and made his fortune in the banking and railroad businesses. Tod made a tremendous impact on Greenwich Point, building a country estate that changed the landscape of the Point and instituting features that foreshadowed its present-day recreational usage.8

Since its inception as a summer retreat for a wealthy industrialist, Greenwich Point has served a focal point for recreation in Greenwich. During the Innis Arden period when the property was under the purview of J. Kennedy Tod, the estate provided the backdrop for boating, swimming, skeet shooting and golfing. While largely a playground for wealthy Tod and his friends and family, local residents were permitted to use of the beaches and golf course until overuse by enthusiastic hotel guests curtailed the latter. The link between Greenwich Point and recreation continued and strengthened when the city of Greenwich became the owners of the property and created Greenwich Point Park.

Tod Tenure and Bequest, 1884-1945

John Kennedy Tod was born in Glasgow on September 11, 1852, to Andrew and Mary Kennedy Tod. In 1868, he sailed to the United States, where he lived and worked for a few years before returning to Glasgow. Back in his native city in the mid-1870s, Tod worked in the iron trade, and spent leisure time playing forward for Scotland’s rugby football team, an indication of his interest in recreational activities – an interest that would define the character of his future Greenwich Point estate. In 1879, Tod permanently immigrated to the United States, where he worked in the New York City investment banking firm of his uncle, John Stewart Kennedy. J. S. Kennedy & Co. was involved in financing construction of the Great Northern Railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the Union Pacific Railway, among other enterprises. After his uncle retired in 1883, Tod reorganized the firm as J. Kennedy Tod & Co., continuing his family’s role in financial enterprises ranging from railroad construction to reorganization of the American Cotton Oil Company. These and other ventures placed J. Kennedy Tod among the wealthy elite of New York who made the Connecticut coast their playground.9

In late 1882, Tod married Maria Howard Potter, whose family boasted an impressive pedigree. Mrs. Tod was the daughter of New York/London attorney Howard Potter and granddaughter of Alonzo Potter, Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania. The Potter-Tod marriage ceremony was performed by the bride’s uncle, the Rev. Dr. Henry Codman Potter, rector of New York City’s historic Grace Church and future Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. Another uncle was William Appleton Potter, who, a few years following his niece’s marriage, would design the Tod estate on Greenwich Point.10

Tod was among the first business commuters who regularly traveled by rail from the Greenwich area to New York City. Following their marriage, the Tods maintained a city residence, but added a country home at Sound Beach (as Old Greenwich was called at the time), where they lived while accumulating their Greenwich Point acreage (in 1887 Tod’s purchase of 30 acres from a Ferris family member completed his acquisition of acreage on the peninsula).11

In 1884, Tod purchased a 40-acre parcel at the western end of Greenwich Point from a Ferris family member, which was the first of his acquisitions on the peninsula. Over the next several years, he bought a number of Greenwich Point parcels from members of the Ferris family. In 1887, he purchased the final 30-acre parcel, placing the peninsula entirely in his hands. This purchase ended Ferris occupation of the land after more than 200 years, and the property soon became known as Tod’s Point.12

After the properties were acquired, construction began on the couple’s summer estate on the Point, christened Innis Arden. Before structures could be built, considerable preparatory work had to be completed. “Joining two small islands with fill, [Tod] built a tide-control gate and created a lake from a tidal marsh. Next came a road around the lake and a causeway to provide access to the mainland.”13 For centuries, Greenwich Point largely had been isolated from the mainland, connected by only a narrow, sandy tombolo that lay underwater at high tide, a situation that hindered development of the Point.

In 1892, the Ferris family granted formal easement to Tod to construct and maintain a permanent roadway across the tombolo. In 1900, he purchased the 11 acres containing the thoroughfare, which came to be known as Tod’s Driftway.14Tod eventually built a causeway along the tombolo to facilitate entrance to and egress from his property, using fill brought by barge from the New York City subway project.

The construction of the main house was completed around 1889; building efforts at Innis Arden continued until 1903. The Tods often hosted the families of relatives and friends at Innis Arden. Some guests arrived by yacht, anchoring at a dock in a cove where the depth could accommodate large pleasure boats. A 200-foot pier connected the dock to the boathouse, where small sailboats and canoes were moored for use by the Tods and their guests.

The Tods also permitted local residents use of their beach for swimming. In addition, they granted area fishermen permission to work the Greenwich Point clam, oyster, and scallop beds, as their families had for generations.15 Innis Arden also provided amusements for those indifferent to water-bound activities. Although no hunting was permitted, there was a skeet-shooting range on the grounds. Swans, pelicans, and ducks populated the lake, which was treated as a bird sanctuary. In fact, during the early twentieth century, Tod’s large flock of imported ducks created trouble for area scallop fishermen because they landed on the Greenwich Cove mud flats and fed on the scallops, decimating the beds. The Tods also kept livestock, including horses, mules, cattle, and sheep, as well as more exotic animals. For a time, they kept a black bear in a cage at the the carriage house/Chimes Building.16

In 1899, Tod installed a nine-hole golf course on some 75 acres on the eastern side of Greenwich Point. This facility may be viewed as a nod to Tod’s home country of Scotland, where golf originated and where sports long played an important role in the national identity. In November 1899, Tod worked with Sound Beach residents to charter a golf club that used his Greenwich Point grounds and adopted the name of his estate. The eponymous Innis Arden Golf Club had 64 charter members who paid $12.50 per month; Tod served as its first president. The Innis Arden course opened in the spring of 1900, and area golfers enjoyed playing there for the next four years. Tod’s generosity came to an end in April 1904, when he objected to the many summer hotel boarders who overran the course, crowding the fairways. Apparently, the area resorts had been advertising the Innis Arden Golf Course as an amenity to attract visitors. At that time, it became a private golf course open only to the Tods’ invited guests. The Innis Arden Golf Club reorganized as the South Beach Golf and Country Club, with Tod, again, as a charter member. A new course was laid out on the Greenwich mainland. Three decades later, Tod’s widow gave permission to the Club to reinstate the name Innis Arden Golf Club for the organization’s mainland 18-hole course.17

The Tods’ benevolence extended beyond the bounds of coastal Connecticut. In 1906, the Tods began loaning a large guest cottage on Innis Arden grounds to Anna C. Maxwell and her student nurses for use as a retreat from their difficult duties and six-and-a-half-day workweeks at New York City’s Presbyterian Hospital. Known as the American Florence Nightingale, Maxwell was a significant figure in nursing history. Among her achievements was the founding of the Army Nurse Corps and the establishment of exacting training standards for student nurses. The Tods’ support of Presbyterian Hospital and Maxwell’s nursing students may be traced to the service of John Stewart Kennedy, Tod’s uncle and business mentor, who was board president of Presbyterian Hospital. Besides donating $1 million dollars to establish a nursing school at Presbyterian Hospital, Kennedy also recommended Maxwell as its director. The Tods’ generosity allowed Maxwell and her nurses to enjoy Innis Arden Cottage and the estate grounds (for a dollar a day paid by each nurse to the school) during the respites that they took from May to December 1906 until 1913. Prior to that time, as early as 1901, the Tods had invited the nursing school staff and students to spend their summer work breaks at the Tod’s “mansion”, Innis Arden House. During World War I the Tods had difficulty obtaining sufficient heating oil for the large Innis Arden House, and they occupied the Innis Arden Cottage for a number of years as their Sound Beach residence. Tod built a grouping of two-room cottages for the nurses toward the western end of his estate, called the “Camp”, and these structures became the leave housing for the Presbyterian Hospital nurses after 1913.18

J. Kennedy Tod died at Innis Arden House on June 2, 1925, at the age of 72. His will stipulated that his widow was to receive all household and personal effects, as well as a life interest in Innis Arden House, where she lived until she died in 1939. She also received the income from a $150,000 trust fund to maintain the estate. The many bequests to relatives, friends, employees, and institutions included a legacy of $100,000 to New York City’s Presbyterian Hospital, which had received considerable support from Tod during his lifetime.19 Following Mrs. Tod’s death, Innis Arden was to pass to the Presbyterian Hospital for use as a convalescent home, operated as the country branch of the hospital’s Medical Center. Patients who had recovered sufficiently from the critical stages of their illnesses or injuries were to be transported by boat to Innis Arden, where they would be established in comfortable accommodations for a period of rest and recovery.20 The amenities available to the hospital were described in a 1926 newspaper article:

The residence is commodious and while it is now the home of Mr. Tod’s widow, it will eventually pass to the Presbyterian Hospital along with the Innis Arden guest cottage, the chime tower, stables, boathouses, servants’ quarters and other buildings. On the peninsula are two small lakes suitable for boating. On the Sound there is a sand beach, three-fourths of a mile long. This beach is especially valuable for the sun treatments and salt water bathing which will be a part of the convalescent program. The variation in the topography of the peninsula makes it possible to have nearly every form of outdoor recreation there. Dr. [Frederic] Brush of the Burke Foundation after viewing the Tod estate said: “This splendid property can be developed into the greatest country convalescent and preventative health plant in America.”21

Apparently, the plan was to be developed after Maria Tod’s death; however, she lived for more than a decade at Innis Arden before dying on September 23, 1939. By that time, the Presbyterian Hospital had established an alternate site on the mainland for its country convalescent home.22 The Presbyterian Hospital retained the Tod bequest for several years, though it did not develop a convalescent facility at Innis Arden. In 1942, the Town of Greenwich leased the estate beach from the hospital for $30,000. The three-year lease gave the public access to 60 acres of beachfront for “municipal bathing.” Three years later, the Presbyterian Hospital sold the peninsula to the Town of Greenwich.23

Town of Greenwich Tenure, 1945 to Present

On January 10, 1945, the Town of Greenwich purchased Tod’s Point and the Innis Arden estate for $550,000. Upon acquisition, the Town changed the name of the peninsula from Innis Arden (or Tod’s Point) to Greenwich Point, a designation it retains, although many continue to call it Tod’s Point. The Town made immediate changes to its new property, including the renovation of the Tods’ formal walled garden, known today as the Seaside Garden, by the Garden Club of Old Greenwich. In addition, the Old Greenwich Boating Association, which later became the Old Greenwich Yacht Club, transferred its headquarters to Greenwich Point.24

After World War II, the Town of Greenwich converted Innis Arden House into 13 apartments for returning veterans’ housing. Rent was nominal. Over the next decade and a half, some 30 veterans’ families lived in the former mansion, enjoying the home and grounds that the Tods had developed. By 1960, however, Innis Arden House was in need of extensive repairs, and the Town decided to demolish it in 1961. Only the “tower” and part of the foundation remain, today forming the base for Greenwich Point Park’s Hanging Garden.25

During negotiations for the purchase of Greenwich Point, the Town of Greenwich assured citizens “that it is our intention and desire that the use of Tod’s Point should be along dignified lines without undesirable concessions or other features which would be unattractive or objectionable to the general neighborhood or to those making use of the property for bathing and wholesome recreation.”26 Accordingly, the Town built or modified amenities for the comfort and enjoyment of the public, including concession stands, first aid station, lifeguard towers, lifeboats, picnic tables, walking trails, boat pier, and marina. In addition, conservation efforts also were introduced, both to stabilize and improve the grounds and to preserve the remaining Innis Arden structures.27

In 1968, a Greenwich residents-only policy was instituted on the Point, but that restriction was lifted when the Supreme Court of Connecticut overturned it in 2001. Today, Greenwich Point is a multiple use recreational park, open year-round to the public during daylight hours. Although the Town has added numerous park features through the years, great care has been taken (since 2004 as the particular mission of the non-profit Greenwich Point Conservancy) to maintain the surviving Tod estate structures, many of which have been repurposed to accommodate modern usage.28

Architecture and Landscape Architecture.

Greenwich Point encompasses the Innis Arden estate and its associated buildings and landscaping. “Innis Arden” substantially survives as Greenwich’s example of the summer retreat designed by architects for wealthy clientele who developed retreats along the coast during the nineteenth century. According to a local report at the time of the creation of the estate, “Mr. Tod is developing a comprehensive plan to make [Greenwich Point] one of the loveliest spots in the state.”29 To facilitate his grand summer estate design, Tod arranged for 30 stonemasons and laborers to be transported from Italy to Greenwich Point. Small cottages were erected on the property for the men to live in while they constructed the roads, foundations for the mansion and original outbuildings, retaining walls, and stonework lining the roads and the cove. These laborers lived on site during the period of initial construction, from about 1887 until 1898. The Tods also lived in one of the cottages during their mansion’s construction in 1887 and 1888.30

The architect for the Tod mansion, Innis Arden House (demolished 1961), was William Appleton Potter, uncle of Mrs. Tod. Potter trained in the Wall Street architecture office of his half brother, Edward Tuckerman Potter (architect of the famous Mark Twain House in Hartford). From 1875 to 1876, William A. Potter was appointed Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury, for which agency he oversaw design production for post offices, courthouses, and other federal government buildings in several states. He was best known for his church and university architecture, including buildings at Princeton and Brown. However, while in partnership with R. H. Robertson (1875-1881), he produced designs for summer homes along the Northeast coast, work that, no doubt, influenced his Tod commission several years later.31

Potter likely designed other buildings constructed in the late nineteenth century at the Innis Arden estate. These buildings included stables, a barn, a boathouse, and a gardeners/ carriage house. Tod added a touch of whimsy to the latter in 1901, fitting it with a 50 foot bell tower with a set of chimes (imported from his home country) that played Scottish melodies as “Annie Laurie” (the architect of the chimes tower was Charles K. Sumner, likely recommended by Wm. A. Potter.) The Tod household included 13 staff members who lived in quarters within Innis Arden House, while the chauffeur, gardeners, and other staff resided in outbuildings on the grounds – possibly the cottages built for the estate’s construction workers.32

In 1903, the Tods added a guest cottage just outside of the entrance to their estate. Innis Arden Cottage was built to house Maria Tod’s widowed sister-in-law and her daughters, though they lived there only a few years before returning to their Washington State home.33 The Cottage was designed in the Craftsman/ bungalow style that was newly-popular after the turn of the century by Katharine Cotheal Budd, an associate of Potter and the first female member of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).34 The architecture field started recognizing women as professional architects in 1888, when Louise Bethune joined the AIA.35 Rather than seek training through a formal academic setting, Budd trained with professional architects, a viable educational path in the late nineteenth century. Not only did she study with Potter, but she also sought training in Paris and with Grosvenor Atterbury, an architect whose early career focused on retreats for wealthy clients.36 This experience likely influenced her work for the Tods. In 1917, the Young Women’s Christian Association retained Budd to design the “Hostess Houses,” buildings constructed to house women visiting male relatives and suitors training at nearby military facilities. These houses expressed Budd’s theories on kitchen design, domestic interiors, and social reform through the creation of a home-like, rather than barrack-like, appearance. Budd was responsible for approximately 70 Hostess Houses throughout the United States. Budd designed several houses in Florida, including the Howey House listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.37

The Tods also employed a female landscape architect, Marian Cruger Coffin. Coffin trained at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s short-lived landscape architecture program and graduated in 1904. Coffin utilized her social and familial connections to secure work after she initially found it difficult to find employment in a male-dominated field. When her cousin, Henry Francis DuPont, inherited Winterthur, he commissioned Coffin to redesign the estate’s gardens, as well as other DuPont properties in Delaware. Coffin eventually counted among her clients Carnegies, Vanderbilts, Huttons, and Mr. and Mrs. Marshall Field. She was made a fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1918.38

Around approximately ca. 1906 the Tods commissioned a formal walled garden at Innis Arden. A modern narrative described the garden:

Each of the four entrances had a green wooden gate leading to grass paths and boxwood parterres filled with roses and perennials. A large circular stone fountain was constructed as a centerpiece for the garden and a vine-covered pergola shaded the overlook with its dramatic view of Long Island [Sound]. The brick walls and the small fountain with the angel relief on the wall are the only remains of the original garden.39

The Innis Arden garden followed “Coffin’s broad view of landscape architecture … [covering] “the design of the entire grounds of an estate instead of merely putting proper flowers in the garden.’”40

The aggregation of the work completed by these architects and landscape architect created a serene retreat for the Tods. The utilization of Shingle-style (and later Craftsman/ bungalow-style) architecture emphasized the resort quality of the property, given the styles’ association with seaside colonies in Long Island and New England. The formal garden hidden within the natural landscape of the property further invoked the idyllic country estate sought by the Tods. The main house was an important part of the estate, but its separation and surrounding landscape permitted its later removal to minimize effects to the setting and configuration of the entire property. The mature landscape and topography of the property ensured views to the main house were limited and provided privacy for those in the main house; the landscape and topography remain extant and the general views remain approximately the same as they did in the nineteenth century. The overall site configuration remains constant, as well; the circulation pattern is tied to Tod’s Driftway and its route near the shoreline of Greenwich Point.

Archeology

Prior to European settlement, Native Americans had occupied the Greenwich coastal area for centuries. On July 18, 1640, they traded the land situated between the Asamuck and Patomuck Rivers to the founders of Greenwich – militia commander Captain Daniel Patrick, wealthy property owner Robert Feake, and Feake’s wife, Elizabeth Winthrop Feake, niece (and daughter-in-law by first marriage) of Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop. The acquisition was bartered for 25 coats. At the time of the purchase, Monakewego (the property now known as Greenwich Point) became the “particular purchase” assigned to Elizabeth Winthrop Feake, and it thereafter became known as Elizabeth’s Neck or Elizabeth Point.41

For over two centuries, the Greenwich Point acreage was devoted to agriculture – cultivation and pasturage – while its shoreline was exploited by oystermen and fishermen. In 1652 early Greenwich colonist Jeffrey Ferris purchased the property from Elizabeth Feake, and members of that family farmed the Point for over 200 years. Many Ferris descendants populate the Greenwich/Old Greenwich locale to the present day.42

Although no systematic archaeological inventory has been completed, investigations at Monakewego, including its Eagle Pond, demonstrate that Greenwich Point was occupied during the prehistoric Woodland Period. Sites there contain intact archaeological deposits with the demonstrated potential to yield additional information about Woodland period subsistence and settlement patterns in coastal Connecticut. Reports of and the ceramics recovered during the 1955 excavations at the Monakewego site often are cited in the regional archaeological literature and continue to be important to understanding regional archeological chronologies. It is clear that application of more careful excavation and modern analytical techniques at the Monakewego site and additional excavation at the Eagle Pond site will yield significant additional information.

Investigation of the site of the main house also has the potential to yield archeological resources. Demolished in 1961, Innis Arden House once stood on the western portion of the lake near the extant boathouse; only the foundation and associated landscape features are visible today. At present, the foundation and the flanking steps consist of large rough-cut stones laid in largely regular courses. Portions of the former foundations for the Innis Arden House have been converted into a “Hanging Garden” dedicated to Helen Kitchel, resulting in concrete caps added to several sections of wall. The intact wall remains and landscape features from the house indicate that the site may include intact archaeological deposits associated with the occupation of the house during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is likely that archeological investigation would confirm this assertion.

Footnotes and Bibliography

Footnotes

7 Rachel Carley, Building Greenwich: Architecture and Design, 1640 to the Present (Greenwich, Connecticut: Historical Society of Greenwich, 2005), 159-166; Greenwich Historical Society, “A Short History of Greenwich, Connecticut;” Diana Ross McCain, Connecticut Coast: A Town-by-Town Illustrated History (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2009), 3, 8-9.

8 Carley, Building Greenwich: Architecture and Design, 1640 to the Present, 166; “J. Kennedy Tod Dies at 72 Years,” New York Times, June 3, 1925.

9 “J. S. Kennedy Dead of Whooping Cough,” New York Times, November 1, 1909; “J. Kennedy Tod Dies at 72 Years,” New York Times, June 3, 1925; ESPN, “Player Profile: John [Kennedy] Tod, Scotland” (ESPN Scrum: Rugby Union), http://en.espn.co.uk/scotland/rugby/player/332.html.

10 “Events in the Metropolis: Three Weddings … Tod-Potter,” New York Times, November 16, 1882; “Howard Potter Dead,”

New York Times, March 25, 1897; Project Canterbury, “Henry Codman Potter, 1835-1908.”

11 Carley, Building Greenwich: Architecture and Design, 1640 to the Present, 166; Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930 (Canaan, New Hampshire: Phoenix Publishing, 1986), 23; White, “What’s in a Name?”

12 Friends of Greenwich Point, “A Chronology of Greenwich Point,” http://media.wix.com/ugd/c0f817_50e4c04cdfc547c9a7fefe85b7df2670.pdf.

13 Richardson and Braitsch, “History of Greenwich Point.”

14 Friends of Greenwich Point, “A Chronology of Greenwich Point;” Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 23.

15 Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 24-25; “Tod Estate Aids Medical Centre,” New York Times, March 7, 1926.

16 Greenwich Audubon Society, A Guide to Greenwich Point, n.p.; Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 24 25; “Ducks Ate the Scallops,” New York Times, August 6, 1907; Richardson and Braitsch, “History of Greenwich Point.”

17 Alex Tyrrell, “Scottishness and Britishness: From Scotland to Australia Felix,” Humanities Research 13, no. 1 (Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian National University Press, 2006), http://press.anu.edu.au/hrj/2006_01/html/ch03.html.; Carley, Building Greenwich: Architecture and Design, 1640 to the Present, 166; Innis Arden Golf Club, “History: An Innis Arden Chronology;” “Golf Club for Sound Beach, J. Kennedy Tod Gives the Use of His Grounds,” New York Times, November 25, 1899; “Innis Arden Golfers Out, J. Kennedy Tod Objects to Summer Boarders Using His Links,” New York Times, April 13, 1904.

18 MacEachern, “Historic Point Cottage Nearing Completion of Renovation;” Suzanne Law Hawes, “Innis [Innis] Arden and a Bit of Presbyterian Hospital History,” The Alumni Newsletter 12, no. 2 (Fall 2011):7, Columbia University-Presbyterian Hospital School of Nursing Alumni Association, http://www.cuphsonaa.com/pubs/Columbia10_11_NCN.pdf; Christopher P. Franco, “The Lost History of Innis Arden Cottage,” Greenwich Magazine, June 2004. http://greenwichpoint.org/innis_01.htm

19 “J. Kennedy Tod Dies at 72 Years,” New York Times, June 3, 1925; “Charity and Friends Share in Tod Estate … Life Interest in Famous Summer Home Goes to Widow.” June 11, 1925.

20 “Charity and Friends Share in Tod Estate … Life Interest in Famous Summer Home Goes to Widow.” June 11, 1925; “Tod Estate Aids Medical Centre,” New York Times, March 7, 1926.

21 “Tod Estate Aids Medical Centre,” New York Times, March 7, 1926.

22 “Mrs. J. Kennedy Tod, Widow of Banker and Niece of Late Bishop Henry C. Potter,” New York Times, September 24, 1939; Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 25; Christopher P. Franco, “The Lost History of Innis Arden Cottage,” Greenwich Magazine, June 2004. http://greenwichpoint.org/innis_01.htm; MacEachern, “Historic Point Cottage Nearing Completion of Renovation.”

23 Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 25; Friends of Greenwich Point, “A Chronology of Greenwich Point;” “Greenwich Buys Tod’s Point,” New York Times, January 11, 1945.

24 “Greenwich Buys Tod’s Point,” New York Times, January 11, 1945; Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 25; Friends of Greenwich Point, “A Chronology of Greenwich Point.”

25 Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 25; Town of Greenwich. “Greenwich Point.”

26 Richardson and Braitsch, “History of Greenwich Point.”

27 Friends of Greenwich Point, “A Chronology of Greenwich Point;” Town of Greenwich. “Greenwich Point.”

28 Ibid; Greenwich Point Conservancy mission, www.greenwichpoint.org.

29 Untitled news item re: J. Kennedy Tod of Greenwich Point, Greenwich Graphic, April 21, 1888.

30 Carley, Building Greenwich: Architecture and Design, 1640 to the Present, 166; Friends of Greenwich Point, “A Chronology of Greenwich Point;” Innis Arden Golf Club, “History: An Innis Arden Chronology,” http://www.innisardengolfclub.com/Default.aspx?p=DynamicModule&pageid=346567&ssid=249384&vnf=1; Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 23.

31 American Institute of Architects, “Obituaries: William A. Potter, Corresponding Member, A.I.A,” The American Institute of Architects Quarterly Bulletin 10, no. 3 (October 1909), 221-222, http://public.aia.org/sites/hdoaa/wiki/AIA%20scans/Obits/QB_Oct1909.pdf; Princeton University, “Princeton History, Number 8, August 89 [Architects],” http://etcweb.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Otherdocs/history.html.

32 Carley, Building Greenwich: Architecture and Design, 1640 to the Present, 166; Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut, The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930, 24; “Tod Heirs Present Estate to Hospital,” New York Times, December 3, 1925.

33 Frank MacEachern, “Historic Point Cottage Nearing Completion of Renovation,” Greenwich Time, March 23, 2011, http://www.greenwichtime.com/local/article/Historic-Point-cottage-nearing-completion-of-1266101.php; Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, “International Archive of Women in Architecture Biographical Database: Katherine [sic] Cotheal Budd,” https://iawadb.lib.vt.edu/view_all.php3?person_pk=2073®ion=&table=bio&cSel=.

34 Frank MacEachern, “Historic Point Cottage Nearing Completion of Renovation,” Greenwich Time, March 23, 2011, http://www.greenwichtime.com/local/article/Historic-Point-cottage-nearing-completion-of-1266101.php; Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, “International Archive of Women in Architecture Biographical Database: Katherine [sic] Cotheal Budd,” https://iawadb.lib.vt.edu/view_all.php3?person_pk=2073®ion=&table=bio&cSel=.

35 The American Architectural Foundation, “That Exceptional One: Women in American Architecture, 1888-1988.” http://www.aia.org/aiaucmp/groups/aia/documents/pdf/aiab092148.pdf

36 Katharine Cotheal Budd Membership Application to AIA, 1924. http://public.aia.org/sites/hdoaa/wiki/AIA%20scans/AB/ Budd_KatharineC.pdf

37 National Register of Historic Places, Howey House, Howey-in-the-Hills, Lake County, Florida, National Register #83001426.

38 Knollwood Garden Club, “The Seaside Garden: History” (Old Greenwich, Connecticut: Greenwich Point Conservancy Collection Files, n.d.); Nicole Briggs, “Palladium Museum Presenting Symposium on Historic Greenwich Gardens.” Greenwich Daily Voice, April 9, 2015, http://greenwich.dailyvoice.com/neighbors/palladium-musicum-presenting-symposium-on-historic-greenwichgardens/ 528564/; Eran Ben-Joseph, Holly D. Ben-Joseph, and Anne C. Dodge, “Against All Odds: MIT’s Pioneering Women of Landscape Architecture” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, School of Architecture and Planning, City Design and Development Group, 2006), 2, 18-20. http://web.mit.edu/ebj/www/LAatMIT/LandArch@MITlow.pdf.

39 Knollwood Garden Club, “The Seaside Garden: History.”

40 Eran Ben-Joseph, Holly D. Ben-Joseph, and Anne C. Dodge, “Against All Odds: MIT’s Pioneering Women of Landscape Architecture,” 19.

41 Greenwich Historical Society, “Founders of Greenwich, Connecticut,” http://www.hstg.org/founders.php; Greenwich Historical Society, “A Short History of Greenwich, Connecticut,” http://www.hstg.org/greenwich_history.php; Robert Marchant, “Born in Conflict, a Town Called Greenwich Emerges,” Greenwich Time, February 21, 2015, http://www.greenwichtime.com/local/article/Born-in-conflict-a-town-called-Greenwich-emerges 6094442.php.

42 Marchant, “Born in Conflict, a Town Called Greenwich Emerges;” Susan Richardson and Amy Braitsch, “History of Greenwich Point,” http://www.friendsofgreenwichpoint.org/#!history-timeline/cvh3; Town of Greenwich, “Greenwich Point,” (Greenwich, Connecticut: Department of Parks & Recreation, 2007), 3-4, http://www.greenwichct.org/upload/medialibrary/3a7/prFA_GreenwichPoint.pdf.

Bibliography (Books, articles, and other sources used)

American Institute of Architects. “Obituaries: William A. Potter, Corresponding Member, A.I.A. (Extracts from Article in Architectural Record for September, 1909, by Mr. Montgomery Schuyler).” The American Institute of Architects Quarterly Bulletin 10, no. 3 (October 1909). http://public.aia.org/sites/hdoaa/wiki/AIA%20scans/Obits/QB_Oct1909.pdf.

Ben-Joseph, Eran, Holly D. Ben-Joseph, and Anne C. Dodge. “Against All Odds: MIT’s Pioneering Women of Landscape Architecture.” Cambridge, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, School of Architecture and Planning, City Design and Development Group, 2006. http://web.mit.edu/ebj/www/LAatMIT/LandArch@MITlow.pdf.

Briggs, Nicole. “Palladium Museum Presenting Symposium on Historic Greenwich Gardens.” Greenwich Daily Voice, April 9, 2015. http://greenwich.dailyvoice.com/neighbors/palladium-musicumpresenting-symposium-on-historic-greenwich-gardens/528564/.

Carley, Rachel. Building Greenwich: Architecture and Design, 1640 to the Present. Greenwich, Connecticut: Historical Society of Greenwich, 2005.

ESPN. “Player Profile: John [Kennedy] Tod, Scotland.” ESPN Scrum: Rugby Union. Accessed December 7, 2015. http://en.espn.co.uk/scotland/rugby/player/332.html.

Franco, Christopher P. “The Lost History of Innis Arden Cottage.” Greenwich, June 2004. http://greenwichpoint.org/innis_01.htm.

Friends of Greenwich Point. “A Chronology of Greenwich Point.” Friends of Greenwich Point. Accessed December 2, 2015. http://media.wix.com/ugd/c0f817_50e4c04cdfc547c9a7fefe85b7df2670.pdf.

Friends of Greenwich Point. “Innis Arden Cottage.” Friends of Greenwich Point. Accessed December 2, 2015. http://www.friendsofgreenwichpoint.org/#!innis-arden-cottage/c2cd.

Greenwich Audubon Society. A Guide to Greenwich Point. Greenwich, Connecticut: Greenwich Audubon Society, n.d.

Greenwich Graphic. Untitled news item re: J. Kennedy Tod of Greenwich Point. April 21, 1888.

Greenwich Historical Society. “Founders of Greenwich, Connecticut.” Accessed December 9, 2015. http://www.hstg.org/founders.php.

Greenwich Historical Society. “A Short History of Greenwich, Connecticut.” Accessed December 9,

2015. http://www.hstg.org/greenwich_history.php.

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018

Greenwich Point Historic District Fairfield County, CT Name of Property County and State Sections 9-end page 24

Hawes, Suzanne Law. “Innis [Innis] Arden and a Bit of Presbyterian Hospital History.” The Alumni Newsletter 12, no. 2 (Fall 2011):7. Columbia University-Presbyterian Hospital School of Nursing Alumni Association, Inc. http://www.cuphsonaa.com/pubs/Columbia10_11_NCN.pdf.

Innis Arden Golf Club. “History: An Innis Arden Chronology.” Accessed December 19, 2015. http://www.innisardengolfclub.com/Default.aspx?p=DynamicModule&pageid=346567&ssid=249384&vnf=1.

Junior League of Greenwich, Connecticut. The Great Estates: Greenwich, Connecticut, 1880-1930. Canaan,New Hampshire: Phoenix Publishing, 1986.

Knollwood Garden Club. “The Seaside Garden: History.” Old Greenwich, Connecticut: Greenwich Point Conservancy Collection Files, n.d.

MacEachern, Frank. “Historic Point Cottage Nearing Completion of Renovation.” Greenwich Time, March 23, 2011. http://www.greenwichtime.com/local/article/Historic-Point-cottage-nearing-completion-of-1266101.php.

Marchant, Robert. “Born in Conflict, a Town Called Greenwich Emerges.” Greenwich Time, February 21,2015. http://www.greenwichtime.com/local/article/Born-in-conflict-a-town-called-Greenwich-emerges-6094442.php.

McCain, Diana Ross. Connecticut Coast: A Town-by-Town Illustrated History. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2009. New York Times.

“Events in the Metropolis: Three Weddings … Tod-Potter ….” November 16, 1882. New York Times. “Howard Potter Dead; The Well-Known Lawyer and Clubman Passed Away Suddenly Yesterday in London.” March 25, 1897.

New York Times. “Golf Club for Sound Beach, J. Kennedy Tod Gives the Use of His Grounds.” November 25, 1899.

New York Times. “Innis Arden Golfers Out; J. Kennedy Tod Objects to Summer Boarders Using His Links.” April 13, 1904.

New York Times. “Ducks Ate the Scallops; J. Kennedy Tod’s Imported Fowl Caused Recent Shortages in Crops.” August 6, 1907.

New York Times. “J. S. Kennedy Dead of Whooping Cough; The Financier and Philanthropist … Rose from a Scotch Mining Clerk to Be a Railroad Man and Banker Worth Millions.” November 1, 1909.

New York Times. “J. Kennedy Tod Dies at 72 Years; Retired Banker … Director in Railways.” June 3, 1925.

New York Times. “Charity and Friends Share in Tod Estate … Life Interest in Famous Summer Home Goes to Widow.” June 11, 1925.

New York Times. “Tod Heirs Present Estate to Hospital; Presbyterian to Make Convalescent Home on Peninsula and Islands in Sound.” December 3, 1925.

New York Times. “Tod Estate Aids Medical Centre; Gift of Country House at Greenwich Adds to Facilities for Care of Convalescents.” March 7, 1926.

New York Times. “Mrs. J. Kennedy Tod, Widow of Banker and Niece of Late Bishop Henry C. Potter.” September 24, 1939.

New York Times. “Greenwich Buys Tod’s Point.” January 11, 1945.

Princeton University. “Princeton History, Number 8, August 89 [Architects].” http://etcweb.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Otherdocs/history.html.

Project Canterbury. “Henry Codman Potter, 1835-1908.” Accessed December 17, 2015. http://anglicanhistory.org/usa/hcpotter/.

Richardson, Susan, and Amy Braitsch. “History of Greenwich Point.” Friends of Greenwich Point. Accessed December 2, 2015. http://www.friendsofgreenwichpoint.org/#!history-timeline/cvh3.

Suggs, Robert Carl. “Excavations at Greenwich Point, Greenwich, Connecticut” Eastern States

Archaeological Federation Bulletin 15, p 13.

Suggs, Robert Carl. “The Manakaway Site, Greenwich, Connecticut” Archeological Society of

Connecticut Bulletin 29 (December 1958), pp. 21-47. Sections 9-end page 25

Suggs, Robert Carl. “The Manakaway Site, Greenwich, Connecticut” Archeological Society of

Connecticut Bulletin 29 (December 1958), pp. 21-47.

Town of Greenwich. “Greenwich Point.” Greenwich, Connecticut: Department of Parks & Recreation, 2007. http://www.greenwichct.org/upload/medialibrary/3a7/prFA_GreenwichPoint.pdf.

Tyrrell, Alex. “Scottishness and Britishness: From Scotland to Australia Felix.” Humanities Research 13,

no. 1 (Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australian National University Press, 2006). http://press.anu.edu.au/hrj/2006_01/html/ch03.html.

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. “International Archive of Women in Architecture Biographical Database: Katherine [sic] Cotheal Budd.” Accessed December 4, 2015. https://iawadb.lib.vt.edu/view_all.php3?person_pk=2073®ion=&table=bio&cSel=.

White, Carl. “What’s in a Name?” Historically Speaking, Greenwich Library blog, May 23, 2012. http://www.greenwichlibrary.org/blog/historically_speaking/2012/05/whats-in-a-name.html.

Wiegand, Ernest A. Phase I Archaeological Reconnaissance Survey of the Greenwich Point Water Main Relocation Project. (December 2006) Report prepared for Department of Public Works, Town of Greenwich, Connecticut.

Letter Report for the Greenwich Point Reforestation Project Archaeological Survey. (May 2006)

Report prepared for the Town of Greenwich Conservation Commission, Greenwich, Connecticut.

Prominent Women and Innis Arden Cottage

Given the early history of Greenwich Point, it is interesting but not surprising that prominent women in American history have played significant roles in its history. Years before young women were encouraged to pursue careers in fields dominated by men, three notable women played important roles in the history of Innis Arden Cottage. These have included Katherine C. (“KC”) Budd, the building’s architect and one of the first women to successfully practice architecture, Anna C. Maxwell, a frequent guest at the Cottage and a pioneer of the modern nursing movement, and Bertha Potter Boeing, a pioneer in women’s aviation who was also a niece of Mr. J. Kennedy Tod and who, with her widowed mother and two sisters, were the first residents of Innis Arden Cottage. KC Budd and Anna Maxwell were the subjects of the Women’s History Month lectures in March of 2012 and 2013, respectively, which were co-sponsored by The Greenwich Historical Society and the Conservancy and held at Innis Arden Cottage. A lecture regarding Bertha Boeing is planned.

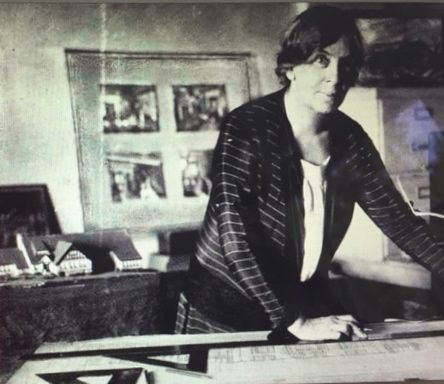

KC Budd

Katherine C. Budd (1860 -1951) studied architecture privately with the founder of the Columbia School of Architecture, William Ware, in 1881 and continued her training at the Art Students League in New York and Paris. As a former pupil of William A. Potter, the architect of the Innis Arden House (the "mansion") and other early buildings on the Tod estate (now Greenwich Point), she was recommended by Potter to design a guesthouse for the Tods in 1903. Ms. Budd was one of the first woman admitted to the New York State Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1916 and the national AIA in 1924.

Anna Maxwell

Anna C. Maxwell (1851-1929) was the founding director of the New York Presbyterian Hospital (now Columbia University) School of Nursing. She was recruited for that job by John S. Kennedy, president of the hospital’s board and uncle of J. Kennedy Tod.

Because of that connection, the handsome stone and shingle Innis Arden Cottage designed by KC Budd became a summer refuge for Anna Maxwell and her nurses between May and December of each year during the Cottage's early history.

Often referred to as the American Florence Nightingale, Ms. Maxwell organized military nurses during the Spanish American War and helped establish the Army Nurse Corps, gaining for nurses military "officer" rank in World War I. Working with the Presbyterian Hospital’s chief surgeon, she organized WW1's first base hospital in Europe and was honored with the French Medal of Honor for her work combating disease in war-torn Europe. She was one of the first women buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Mr. Tod and his wife extended the hospitality of their estate to Ms. Maxwell and the nurses of the Presbyterian Hospital for many years, first at Innis Arden Cottage, and later at a cluster of buildings built on the west side of Greenwich Point expressly for that purpose, which was known as the "Camp".

Bertha Potter Boeing

Bertha Potter Boeing (1891-1977) had been a young girl living in Tacoma Washington when her father, Howard Cranston Potter, brother of Maria Potter Tod, died tragically in a fall off the high cliffs at Cliff House in San Francisco. His death was high profile and mysterious, and was covered on the front pages of newspapers nationwide. Soon after his death, Mr. and Mrs. J. Kennedy Tod built Innis Arden Cottage as a guesthouse for Maria Tod’s sister-in-law Alice Potter and her three daughters, who attended Rosemary Hall in Greenwich. The middle daughter, Bertha, loved the Tod’s seaside estate known as Innis Arden. Bertha eventually moved back to Washington State and married William Boeing, who became the founder of Boeing Aircraft, United Technologies and United Airlines. Bertha herself was a force, very involved in the family business. She was a friend and mentor of Amelia Earhart, and was also responsible for arranging for the first women to become flight attendants, a career that had previously been enjoyed only by men. Bertha required that her flight attendants, who first worked at United Airlines, also be trained nurses. Bertha christened several of the most famous aircraft developed for and used in WWII, and Bertha and William Boeing later named a large real estate parcel they were developing on the Puget Sound in Seattle “Innis Arden”, reflecting Bertha's love for the special place she lived as a child. Today, Seattle's Innis Arden is an upscale neighborhood in Seattle that goes by that name.